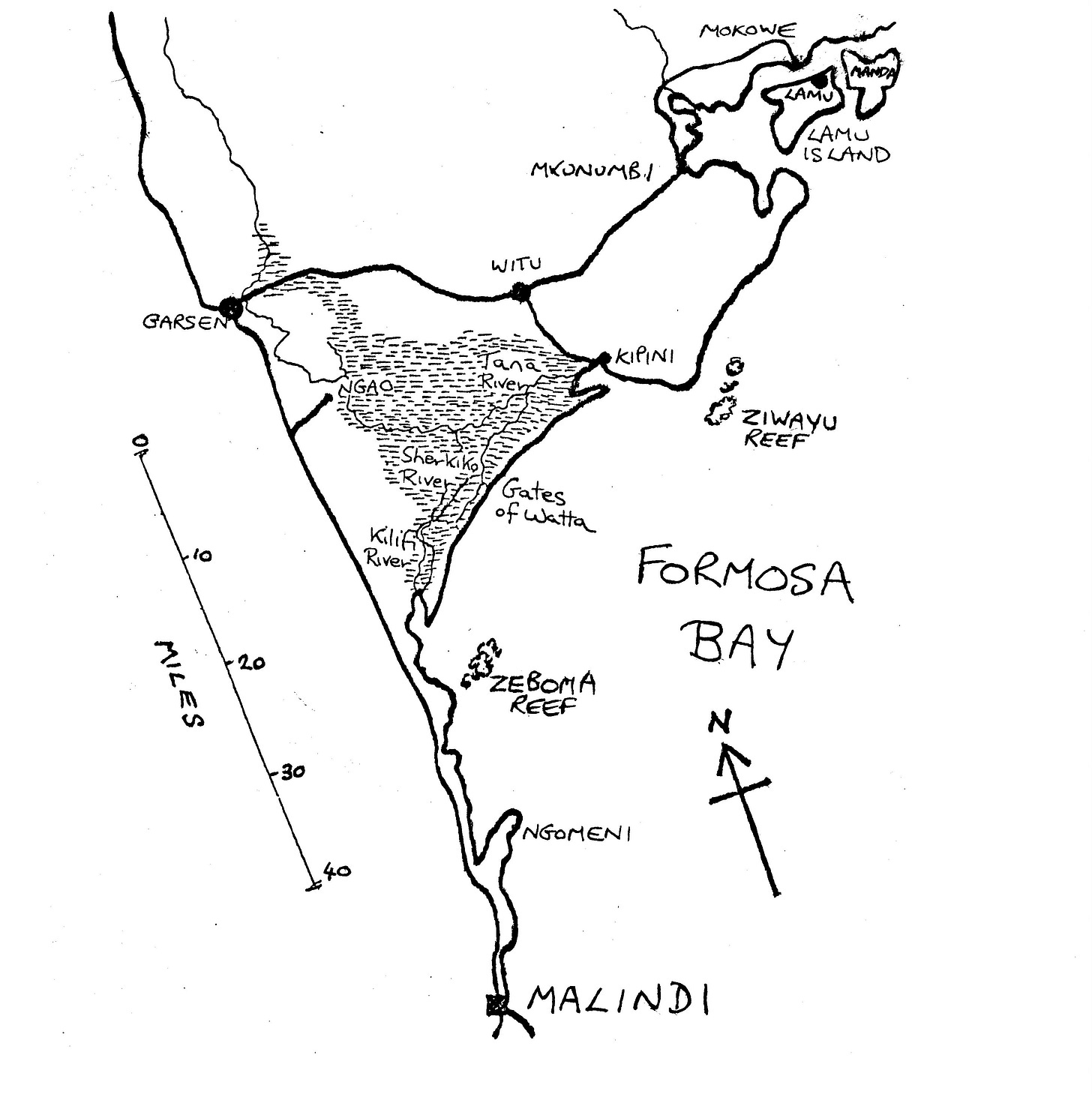

(1979) As I have said, Alex, Sally and I operated our seasonal luxury tented camp near the estuary of the Old Tana River, along the Kenya coast between Malindi in the south and Kipini in the north. Looking at my hand-drawn map from 1979, you can see Gates of Watta marked, and our camp was located about half a mile inside the estuary mouth, on the north bank of the river.

The Tana River is over 500 miles long, Kenya’s longest river, and it rises up-country in the Aberdare Range of Mountains. Roughly triangular in shape, the 500 square mile Tana River Delta has its apex at Lake Bilisa (north of Garsen), and its base is a 30-mile-long stretch of beach fringing Formosa (Ungwana) Bay and stretching from the mouth of the Kilifi River in the south-west up to Kipini in the north-east. This low-lying area is hemmed in by higher land to the east and west and is bounded to the south-east by a dune system that borders the Indian Ocean. Botswana’s Okavango Delta is more famous, but Kenya’s Tana River Delta is one of Africa’s most important wetlands. It contains a range of different habitats, and it is home to a variety of birdlife as well as elephant, Cape buffalo, lion, hippo, crocodile, wild dogs, topi, Tana River red colobus, Tana River mangabey and a variety of other wildlife.

The only widely recognized tribe who inhabit the delta are the Pokomo, and they farm the riverbanks of the riverine forest. Other smaller groups include members from the tribes and sub-tribes of Banjuni, Boni, Giriama, Malakoye, Munyoyaya, Orma, itinerant Somalis, Sanya, Wakone, Wardei and Watta (a.k.a. Wasanje). In the 1970s, the Watta were a fearsome and widely scattered tribe of hunter/gatherers who hid in the forests and hunted elephant with poison arrows. They were seldom encountered, and an elderly professional hunter had once confided to us that he was probably the last white man to catch a glimpse of one of the Watta, and that this was back in the early 1960s.

The mouth of the river has shifted many times and today, the main river follows an artificial course. More than a century ago, the flooded river cut through into a canal dug for navigation from Belazoni on the main river into the River Ozi (itself possibly being an old course of the Tana River). As a result, the river flows directly into the estuary at the town of Kipini, rather than into the complex system of channels that lead to its old mouth at Mto Tana, about ten miles or so south along the coast from Kipini and near which we had established our safari camp

In the late 1970s, Kipini was no more than a cluster of thatched huts around a dilapidated cement mosque; that was the entire village. It was an End of the Road – or in this case, River – sort of place, a sleepy village where nothing much ever happened. At least nothing did until a handful of mzungus turned up there: us! Its main claim to fame was the nearby prison, a bleak and heartless place where the country’s worst criminals were sent. But they did have cold beers and radio communication, so the villagers tried hard to befriend the prison warden and the guards. The residents of Kipini had the worst reputation for thievery, double-crossing and general chicanery, and I can attest that it was truly well-deserved.

When not in Malindi on business or on leave, my home was ‘under canvas’ and located deep in the heart of big-game country in the Tana River Delta, just behind the high sand dunes that fringe this part of the coast. Our luxurious safari camp boasted huge living tents with en-suite bathrooms, a magnificent dining tent serving gourmet cuisine, silver and crystal, a chef, a headman and a liveried staff of eight or more to cater to our clients’ every wish. Alex designed the staff uniforms which consisted of a white kofia (brimless cap), a white tunic jacket with high collar, black-and-gold epaulettes and black buttons, bright blue long trousers, white plimsoll shoes and a red sash tied around the waist. The staff loved dressing up in these fancy uniforms, and they wore them with pride. In those days, you could go into Malindi to an Indian-owned tailor’s shop on a Monday and order uniforms like this, for pickup on Thursday. There would be a stiflingly hot room out back, crowded with Africans, both men and women frenziedly operating ancient foot-treadle Singer sewing machines, hurriedly trying to fill the boss’s orders.

One day when we had ventured up-river from our Tana River Delta Camp in Lufty, our motorized inflatable Zodiac boat, we rounded a bend and saw a huge African standing in the mud of a falling tide. Our appearance startled him, and he began to clamber up the muddy bank, soon disappearing from sight into the tall grass. Since there were reputedly no tribes living in this part of the Tana River Delta, it surprised us to see him, and Alex immediately twisted the throttle of the outboard engine to full power, as we raced to the riverbank. We beached on the muddy slope of the riverbank, and Alex cut the engine, loudly calling out that we were friends… rafikis. Just as we were about to give up, the grassy stalks parted, and a huge black face emerged. It took several minutes for Alex to convince the man to show himself fully, and it was probably the presence of Sally in the boat that helped ease his fears. Gradually, we were able to coax him out of the tall grass and to come to sit within a few feet of us.

He did not speak much Swahili, but we found we could communicate with him, using a few words of Swahili and a lot of hand gestures. It turned out that his name was Bloni, and our research later on concluded that he belonged to the Watta (a.k.a. Watha, WaLiangulu, Wasanye) tribe, a wild tribe of hunter-gatherers who shot game with poison arrows and harvested fish and crab from the river. ‘Watta’ is a contraction of a longer expression which means ‘to go with the will of god.’

Their origin was Cushitic, and they originally came down to Kenya from as far north as Ethiopia, competing with the cattle owning tribes of north-east Kenya and losing out to them, eventually turning to hunting and gathering. Some of the tribe moved down to settle in the vast Tana River Delta, while others moved further west and ended up in Tsavo, and ideal environment for hunting and ambushing game.

In those early days, Tana River Delta and Tsavo had one thing in common: many many elephants! Adept with the Watta version of a longbow and carrying a quiver of poison-tipped arrows, an elephant was no match for a skilled Watta bowman. Young boys were trained from an early age by the elders, learning how to creep up on a feeding elephant. A boy’s transition to manhood was marked by him being able to sneak up behind an elephant, pluck out a black bristly tail hair, and escape before the enraged elephant whirled around, grabbed him with its trunk and dashed his brains out against a nearby tree. It happened.

Once fully trained and proficient with the bow, the young hunter would venture out alone into the bush, track a target elephant, creep up to the animal and then shoot a poisoned arrow at close range, deep into its flank. Then it was just a matter of following the ailing beast until it dropped, perhaps a day or two later. The meat from a single elephant could feed an extended family group of twenty to thirty members for up to two months, once the meat was smoked and dried.

We soon learned from Bloni that his tribe had not seen a white man in this area since Independence in 1963. Back in Malindi, we had been told that the Watta were extinct, a tribe of legend, but here we were face to face with one of them. Bloni was a large man, certainly over six feet tall and built like a linebacker. As I looked at this huge man, I noticed how big his bare feet were. Not only were they the biggest feet I had ever seen, but they were almost triangular in shape, since he had never worn shoes. Bloni’s favorite delicacy was the crabs he harvested from the estuarine river, and his wide feet were perfectly suited for roaming the muddy slopes of the riverbank at low tide, as he hunted for crabs.

The crabbing technique he used had been handed down, father-to-son, over generations. Starting at low tide, he would first look for sizeable crab holes in the sloping mud, planting a small stake firmly into the mud next to each one. Once he had staked out some twenty to thirty holes in this way, he retraced his steps, this time tightly tying a three-foot length of hemp rope to each stake. The end of each rope was wound and knotted around a strip of dried fish and then dropped on the mud, within a foot of the hole.

All Bloni had to do now was wait out a full cycle of the tide. Once high tide came, each crab came out of its hole to forage, soon found the piece of dried fish and then pulled it back into its hole to be devoured later at leisure. At the next low tide, Bloni went out to survey the muddy slope. Where he saw a hole with the hemp rope pulled down into it, he knew a crab was down there. His technique was to ever-so-slowly wind the rope in, knowing that the crab was following its ‘moving dinner’ up to the mouth of the hole. Once the crab was out of the hole, Bloni deftly scooped it up and tossed it in his net bag. In this way, he could gather twenty or more sizeable crabs within an hour.

Anyway, Bloni joined our staff, learned to wait at table and even finally consented to wearing shoes; the Bata safari boots we had specially made for him in Nairobi, because Bata (the Kenyan shoe company) had no shoes large enough to fit him.

When we did not have clients in camp, I fished and caught huge tewa (grouper) in the estuary (photo inset). I stalked game on foot. I talked to the natives who suddenly materialized out of the bush and came to squat by the fire, telling me wide-eyed tales of local giants and goblins, and then nonchalantly eating our food. I made palm beer, and I read stories of Africa. Later on, I would explore much of Kenya with my girlfriend Nicky – Sally’s younger sister, and a talented water-colorist - and I took photographs to my heart's content. Sadly, most of my Kenya photos from that era in the late 1970s were lost in the shipwreck of the Tafuta Tu, a gripping true-life escapade that you can read about elsewhere. (to be continued)

Wonderful stories and adventures Andrew, so interesting and entertaining!

Andrew--Amazing detailed adventure from a bygone era !